Tobacco dominated daily life; it was brutal row work plowing behind a mule, planting, suckering and worming, “That was a nasty job; you smushed the worms between your thumb and fingers.” The Lawsons cooked on a wood stove, but added an electric stove after a good sale of tobacco. There was electricity but no well or plumbing. The purchase of a wringer washer and Shorty’s invention to collect rain water to wash clothes revolutionized weekly life. But still only a foot tub was available for bathing, and a bucket was used to wash hair. Marvin Finn spoke for most folks, “There were plenty of Christmases I never seen me a toy.” These and other stories paint a fairly complete picture of everyday life of the Black tenant farmer.

“Momma could do magic with nothing. There never seemed to be enough of anything. Some of us seem to forget so easily that we were out there somewhere or nowhere.” (Albert Lee Wagner)

Girls Bedroom: Life Through the Seasons:

The museum utilizes each of the six rooms to depict a theme representing Shorty Lawson’s life and his values:

Girls’ Bedroom: Life Through the Seasons;

Kitchen: Cooking, Eating and Cleaning;

Room Off the Kitchen: Food Production and Washing;

Shorty and Annie’s Bedroom: Family Values and Joys;

Big Room: Work and Prejudice; and

Boys’ Bedroom: Snakes, God and the Devil. Each room can be accessed for a short description of that theme.

Summer

The Lawsons lived by seasons. Summer was tobacco season. It was sweltering hot. As a tenant farmer Shorty Lawson share-cropped 30 acres of tobacco on halves, netting about 4,000 dollars, maybe even 5,000 dollars in a good year, after all his crop and living expenses for that year were paid. That was during the 1950s and 1960s.

After planting and replanting, tobacco had to be weeded, hoed, plowed, laid by, wormed, topped, and suckered. When Shorty started farming, all this was done by hand. Later untested chemicals like MH30 did the suckering. You pulled tobacco from the ground up, in 90-degree heat and 90-percent humidity. Then you cured the tobacco. As a boy Shorty cured with wood. You had to sleep at the barn to keep the fire going.

Shorty did the planting and plowing by himself. He and Randy, the farm owner’s son, replanted. His older boys helped in all the field work. Women and girls helped weed and strung tobacco at the barn.

Jasper and Irene Fergus lived in the big house, but Jasper had suffered tuberculosis, and they were too old to do much demanding work. Still Jasper was skilled at curing tobacco, and they helped worm tobacco. “Now that was a nasty job. You killed the worms by smushing them between your thumb and fingers.” (Carolyn Lawson)

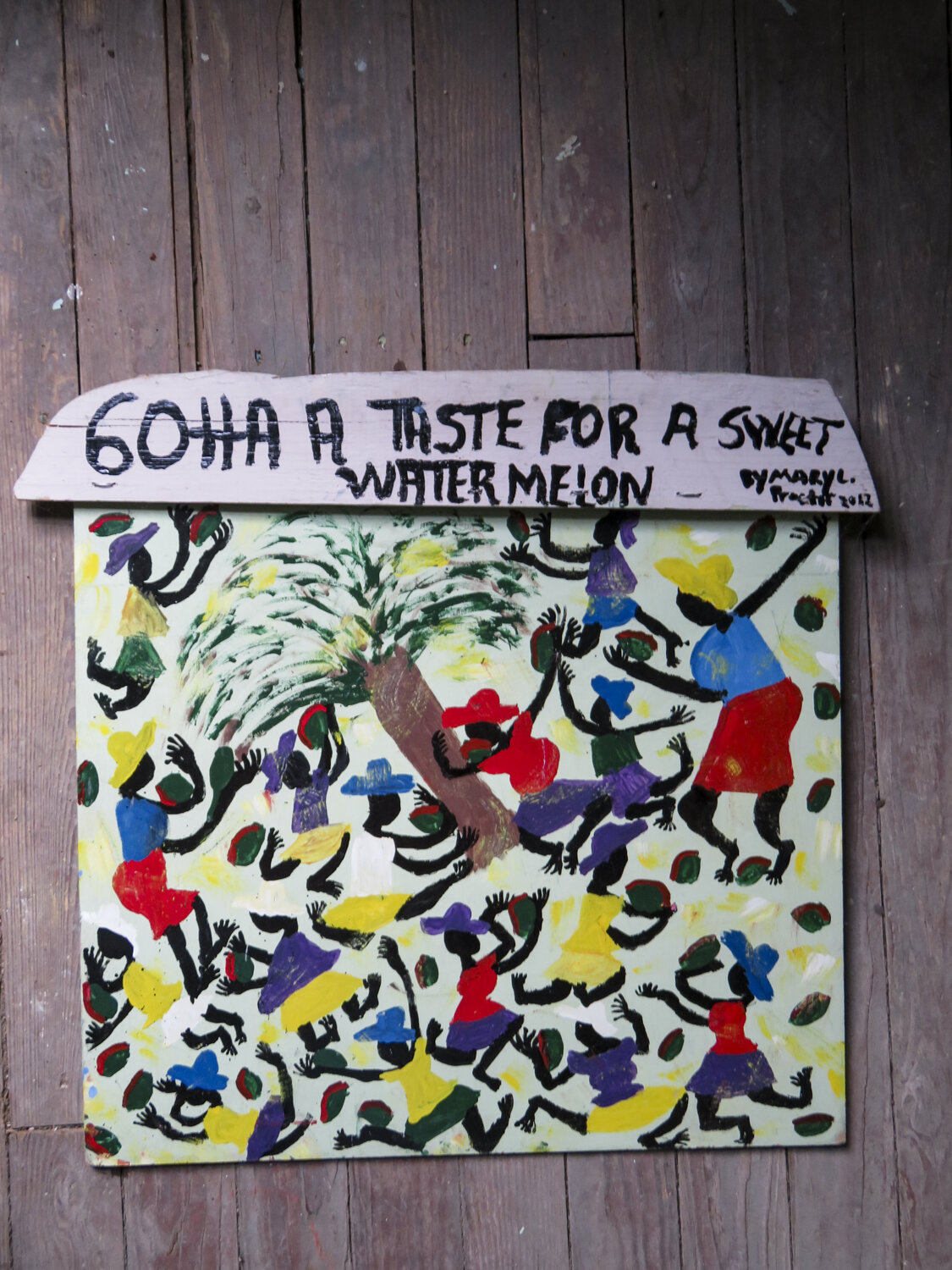

Shorty and his family worked tobacco five and a half days a week, knocking off at noon on Saturday. Then they worked the vegetable garden, washed clothes, and cleaned the house. Shorty often went to town. Everyone sought a place to cool off from the heat. Saturday afternoon most of the family went fishing at the old pond. “We bank fished, never in a boat. I liked a cane pole best. We caught bream, bass, crappie, and catfish, almost always enough for several meals. We kids also fished the creek. And we always had a watermelon patch. Some years it was over half an acre. When watermelon came in, we had more than enough to go around. You could go to the patch and get you one, but you couldn’t waste it.” (Carolyn Lawson)

Fall

This was a season to slow down and get ready. Getting ready for school, for hunting, to fix up, and to buy something special.

Fall was the only time of year that the Lawson family had extra money to spend. After tobacco was sold and debts settled, they had several thousand dollars. The rest of the time they lived on credit and weekly advances from Randolph. Shorty and Annie would figure out what purchase would most improve their lot. Of course, winter shoes had to be bought for the whole family and some school clothes for the children, but each good year there was money left for something major like an oil-burning stove to heat the bedroom or an electric stove for the kitchen. After new clothes, shoes, furniture and Christmas gifts were bought, they still had about $2400 in1967.

At the first killing frost the world turned red, yellow and orange. The big tree in the front yard at Jasper and Irene’s started dropping its leaves, exposing its old limbs, twisted from years of struggle as the only living thing in the swept yard. But Shorty was attending to other trees. He needed to make wood, enough to heat the house and feed the cook stove for the whole winter. He might cut some good-sized oaks or find some trees that a storm had already felled. Other folks might pause from work if a neighbor or stranger passed by, but Shorty seldom stopped. After school and chores, the girls and youngest boys would play with their pets, swing, or play basketball until Annie called them to help get in the wash from the clothes line.

Fall also was the time to repair tools and equipment that had been damaged or broken during tobacco season. Nothing was thrown away. All the mule collars, harness and plows would be patched and hung up out of the weather. And when all the work was caught up, Shorty would get his dog and go hunting, mostly for rabbits. He also hunted squirrels.

Winter

The first really cold spell in December was hog-killing time. You had to wait for freezing weather so the meat wouldn’t spoil. Shorty would get a big fire going under the scalder; Randolph would shoot each hog with a 22 and cut the throat with a butcher knife to drain the blood. After scalding the hog in boiling water, they scrapped the hair off with knives and tin can tops, washed the hog down, cut up the meat, salted it down, or ground it for sausage. Randolph and Shorty went halves on the hogs, Randolph usually getting the choice ham. This provided both families enough pork for the whole year.

Hog killing was an exciting day. There were jobs for everyone from the youngest to the oldest, and they all knew that supper would be a feast of fresh sausage, chitterlings, and tenderloin. Winter weather varied from bitter cold one day (minus 9 degrees F) to spring-like the next (80 degrees F). There were big snows every year. Schools closed for weeks at the time. The children had a big time, but Shorty had to keep up with firewood and tend the animals. Most of the house was cold. The kitchen was the warmest room, facing the sunny south, out of the north wind, heated by a fireplace roaring hot and the cook stove full blast. Eventually Shorty got an oil-burning stove in his and Annie’s bedroom, but the rest of the house had no heat. The boys’ room was icy cold, and snow drifted into the living room, but they stayed pretty healthy. Shorty was never so sick he couldn’t work. And they never had to worry about freezing pipes; they had no plumbing.

Christmas was special for the family. Randolph brought a whole box of apples, oranges, and candy. The children believed in miracles, the Angels of the Lord, the miraculous birth of Jesus and Santa Claus. And Santa always brought some small gifts for the children, even in bad times. Toys, store-bought or homemade, were scarce. You might get a pull toy with wheels if your Dad or Uncle were handy, but “I remember a lot of Christmases when I never seen me a toy.” (Marvin Finn)

Spring

The birds knew it was Spring before anyone else did, all kinds of birds and bright color ones, building nests, making a home, singing their hearts out. If you got a stretch of warm days, the world suddenly sprouted to life, turning pink and pale green overnight, with sweet sights and smells of flowers popping out of the ground. “I remember there was a pear tree up about where the power pole is now, a real pretty tree when it bloomed, and good pears too.” (Carolyn Lawson) Even the old tree over in Jasper’s yard that everyone thought was dying last fall had chartreuse leaves. The sky welcomed Spring with big, fluffy, cotton-ball clouds. Tools got brought out for the season. Walter Bowes cranked up his saw mill at the end of Tom Bowes Road.

Soon every creature was preparing to have babies. The Wood Duck laid her eggs deep in a hollow tree late in February, and the family tested the water the day after the last duckling hatched in March. More than half the babies got eaten by predators. The opossum carried her babies in her pouch for over two months, then they hitched a ride on her back in late Spring. Mr. Rooster was abandoned by his wife and had to raise nine chicks by himself. Ms. Fox had two frisky pups, one larger and far more adventurous than the other, that played at the edge of the woods. They seemed to keep their den just out of sight but close enough that they could steal to the chicken house when folks weren’t looking.

The Lawson family plowed the ground and planted the summer garden in neat rows just north of the house. But the major work was breaking land for tobacco and other field crops. When Shorty was a small boy, this was done with mules pulling a wooden plow, but at the Bowes Farm he had metal plow points, and in the last years of his life most Spring cultivating was done by tractor.

Cooking, Eating and Cleaning: A Lot Going on in Annie’s Kitchen

When Shorty and Annie married, she was already a good cook. She ordered this room and the family diet. Often the family was doing lots of different things besides cooking, all at the same time: talking, telling stories, playing, doing homework, eating, cleaning, and washing up. The kitchen felt like it would explode from the energy of so many activities. Once Annie sent Fernell to get water; he came back smelling like a skunk. He had run into one on the way to the well. Nobody wanted to sit near him or drink the water he brought back, but the water didn’t really taste like skunk. The others teased him until he got real mad.

When Annie was cooking something special like greens and cornbread, or just-caught fish, there were always kids hanging around waiting for it. When she made preserves or did canning in summer, she would get the children into a production line, sort of like a factory, but not so organized. In fact, there was a lot of disorganized fooling around. “She wasn’t hard on us, but we did what she told us.” (Carolyn Lawson) Like most women around Hesters Store, Black and White, Annie used a lot of lard that made her cooking delicious and dangerous.

“The kitchen was also where we took baths and washed our hair most of the time. In winter it was the only warm place. Since we didn’t have plumbing, some of us, usually the older ones, would run over to the well at the big house and get enough buckets to make a bath. The little ones would race after us, make it a game even though it was work. Mama would heat the water and store it on the stove. Then we took turns taking a bath in a big foot tub. I would wash my hair in a bucket or tub, too. That was just how life was. Even without running water it was the best time of my life.” (Carolyn Lawson) In summer the children would bathe in the kitchen or out in the room off the kitchen. It had a cement floor so it was no problem to clean up water that got splashed out. The older brothers and sisters helped bathe the younger ones and the baby.

Please Pull Up a Chair

Join us for a while at the kitchen table. We’ll cook up something for you to think about. “We look back that we may learn wisdom from experience.” (Anna Julia Cooper) Look around to see what is going on. This is Annie’s place, and it extends from here to the pantry and all the way to the garden, clothes line, and chicken coop. She was not bossy, but everyone minded her as she went about kitchen work. She might send a child to get in firewood or feed the chickens and she expected that person to be back directly with wood or feed the chickens without the rooster complaining about supper.

In summer she made pies after the children picked berries. Everybody loved Annie’s pies. She was sort of the Pie Lady of Tom Bowes Road. “We competed to find the best blackberry bushes and get the most, the real black fat ones, and those in the tallest bushes. The little kids mostly ate the berries as fast as they picked them.” (Carolyn Lawson)

Imagine that Annie is at the wood stove on a Saturday, scrambling up some eggs, fixing enough to feed breakfast to each and every hungry mouth. All the children are running in and out or, in winter, huddled around the fireplace, waiting for some eggs and sausage or bacon. “When I was a baby, Mama did all the cooking, but later we got an electric stove, had two stoves, she cooked on the wood stove and I cooked too, on the electric stove. It sat right there where the plug is, one cooking on one side of the room, one cooking on the other side. In summer we cooked mostly on the electric stove, winter the wood stove because it heated the room.” (Caroline Lawson)

“All I claim is that there is a feminine as well as a masculine side to truth; that these are related not as inferior and superior, not as better or worse, not as weaker or stronger, but as complements- complements in one necessary and symmetric whole.” (Anna Julia Cooper)

Everybody Had Chores in the Morning

“I had to milk the cow, wash up, get dressed in school clothes, eat breakfast, find my books and lunch, and run up the road to catch the bus. Some years the bus came down our road, but other years the route was just on the Gordonton Road so we’d have to run over a half mile to meet the school bus.” (Carolyn Lawson) Everyone wore hand-me-downs. “Other families in the community gave us hand-me-downs. That’s what I mostly wore, but you could look real nice in hand-me-downs. We always had what clothes we needed.” (Carolyn Lawson) Second hands and patched hand-me-downs was what most people, Black and White, wore out here, even families that had more money.

Although the kitchen was the women’s place, they relied on Shorty and the boys to make repairs to leaks in the roof and to build cabinets, shelves, and things like that. Shorty was creative in making things from scraps and stuff he found. Every once in a while something Annie needed didn’t get done; she would get short and raise her voice if the boys didn’t fix a broken drawer or bring in the stove wood. The feeling of slighted womanhood is unlike every other emotion of the soul.” (Anna Julia Cooper) You might hear Annie call out, “I can’t cook until you get in the firewood.”

“A lot of this stuff my people want to forget.” (Richard Roebuck) The Lawsons were farmers, gardeners, hunters, and gatherers. Everyone did their part, but the children knew that Shorty and Annie would always try to find a way to take care of them no matter what. There was certainty in that. They grew plenty meat and vegetables, and, if need be, they could catch things from the woods or pond. Rabbits, bullfrogs, big fish and small fish provided many a meal when food was scarce. There were wild grapes and berries in season and the great pecan tree. It usually provided a gracious abundance of nuts waiting to be picked up. “That was just the way our life was.” (Carolyn Lawson)

Room Off the Kitchen: Food Production and Washing:

This was the first room added, the lumber cut up at Walter Bowe’s sawmill. The family was outgrowing the house and needed an enclosed porch to store firewood, food stuffs, and water fetched from the big house. Outside seemed a Peaceable Kingdom, all the animals living in harmony with the family. Reality was everyone trying to eat somebody else. Shorty and Randolph grew a lot of food together. Randolph would buy a bunch of little pigs. “Daddy would fatten them up with slop, kitchen scraps, anything going to waste.” (Carolyn Lawson) They always grew enough to share with others, load the truck full of corn, tomatoes, or watermelons and deliver food to shut-ins. “I always thought Randolph was a smart man; I don’t know why he grows all that food just to give it away.” (Sam Lawson)

It was a joyful day when Shorty bought a deep freeze, sat it right here, filled it up. Annie always canned, now she could freeze vegetables and game the boys got hunting. And there were plenty fish and turtles in the pond. Their family didn’t eat turtle, but a relative did so they’d freeze snapping turtles until he came by. Annie raised chickens. They weren’t pets, but the children played with them and fed them. Annie would kill fryers for special occasions, old hens for chicken and dumplings. She’d wring their necks, pull off their heads; they’d run around with their heads off.

Every so often a fox would steal a chicken. Racoon the worst; he’d bite off the heads, just leave dead chickens everywhere. Once a snake got a bitty, had him in his mouth. Randy grabbed that snake, choked him until he gave up the chick. The chick lived. Everybody hunting, using their skills to feed their families. The fox was scary bad and not very smart in bedtime stories, but Shorty thought different, “Fox eats plenty rabbits and a chicken if he can, but if rooster doing his job, he’d make a fuss, we’d chase old fox away. A smart rabbit stay close to the briar patch. Natural, good or bad I don’t know. Old fox kills only what he eat, he plenty wise, most like a ghost, you see him but you don’t.”

Clean Clothes and Fresh Milk

Some chores started in this room and finished in the yard, often back-and-forth from outside to inside. In the first years of marriage washing clothes was done with a tub and washboard. It was hard, time-consuming work, back-bending, arm-tiring, and hand-rending, especially when field work occupied you all week. Getting everything on the line to dry was cause for celebration.

Getting a wringer washer was cause for an even bigger celebration; but remember the Lawsons didn’t have running water. Shorty had to innovate. He set up 55-gallon drums right outside to catch rainwater off the roof so Annie could fill the washing machine and rinse basin with soft water. She filled the washer with clothes, water and soap; plugged into the electric outlet; and the washing machine did the back-bending, arm-tiring, and hand-rending work. She rinsed in the basin with fresh rainwater, then ran clothes through the wringer to squeeze out excess water. It worked sort of like a spin cycle does today. The clothes were ready for the clothes line to air-dry.

The Lawsons also used this room in making milk and butter. Jasper needed one of the children to milk the cow, but none of the boys wanted to do it; Carolyn volunteered. “You had to get the cow used to you else she wouldn’t stand still, kick over the milk pail, all sorts of trouble. I liked milking.” (Carolyn Lawson) When done, she brought the milk in here. Sweet milk went in the refrigerator. Annie and the girls would churn some of the milk to make butterfat and buttermilk. Up-and-down work, churning tested your endurance unless you could make it a game and get the boys to play. To make stick butter Annie set the butterfat into a mold, squeeze out all the liquid to get the butter to set up.

This room was never weather-tight. It kept rain out but not heat and cold. Birds would come to make a nest; they’d get scared away. Blue racers came in and out as they pleased, eating insects. Dirt daubers would build a mud village and set up house in a day or two.

Make Anything You Need

Shorty didn’t consider himself an artist in any sense of the word, but he was creative in practical ways. He could innovate, adapt or repair anything he needed from what he had at hand. He made handles for saws if one cracked. With wire he extended the life of a tool long after it had expired. It was important to improvise on the spot. When something broke, you didn’t call a repairman or go to town for a replacement. A whole day of work would be lost, plus there wasn’t money to pay somebody else to fix it or buy a new one. Shorty’s creative genius was repairing things immediately with integrity using scrap wood, leather, a piece of old metal, wire, nails, nuts and bolts, put together in unconventional form. Most people could only imagine using materials how you were supposed to.

Shorty knew that a repair had to function, and it had to last. How it looked wasn’t his primary interest, but, most of his homemade or repaired items possessed genuine beauty. “Shorty’s ability to create something beautiful from found objects made a lasting impression on all of us.” (Randy Hester) Consider a homemade ax handle. Shorty and Randolph found a perfect ash or hickory tree, a foot diameter, quartered the green wood with the grain, roughly shaped each handle to size. With a draw-blade and pocketknife, they smoothed a tree into a fine ax handle.

When all other farm work was caught up, their attention turned to “improvements” like adding this room. Again, they only used the materials found on the farm. Each winter they fixed things up, added rooms or sheds, making the Lawson’s house right nice. Shorty made his own rabbit gums, using a time-honored design. The hard part was getting each detail exactly right so that the rabbit would trip the trap door when he went to get the apple put in the back for bait. The women also crafted things for domestic work. The youngsters needed something to tote the food crops from field to home. There was usually someone who could make whatever you needed from what they got.

Shorty and Annie’s Bedroom: Family Values and Joys:

Shorty and Annie were newly married when they moved into this house. They were very practical love birds, a good match: a rough man’s man and a lovely, sturdy woman. “When we came in from the field, Shorty would seek her eye and greet her in his tough sort of way, didn’t acknowledge anybody else.” (Randy Hester) Annie’s family was from here, the Bradshers, the most respected of families, all related to Preach Wiley Bradsher. Shorty was from a more complicated family over near Leasburg. “I knew all those Lawsons and one of their half-brothers, Larry Dixon. He lived with Shorty’s family. All hard workers, but Shorty more so.” (Donald Hester) “Larry was the artist of the family.” (Carolyn Lawson)

In this bedroom Shorty and Annie tended their babies and raised up their children. Shorty was a leader. He was first to start a job and last to quit, whether it was crop work or chores. He expected his boys to pitch in from an early age, and without foolishness. Annie was the nurturer. She was gentle, but she disciplined the children if necessary. “The boys went skating on the pond one real cold spell, frozen over. That was against Daddy’s rules. The boys fell in, came home soaking wet, all of them got a whipping.” (Carolyn Lawson)

Whoever was the baby slept in the cradle at the foot of their bed so Annie could nurse him at night. “I remember Cisco sleeping in that cradle. He’s dead now.” (Carolyn Lawson) Annie was like a mama bird, teaching her babies little things and to obey. She taught them from the Bible, but plenty was just practical lessons like working hard and finishing school. Lacking much school education themselves, Shorty and Annie knew the world was changing. They were strict about the children going to school so they would make something of themselves.

Who Paints the Family Portrait?

Renowned artist Charlie Lucas made a Lawson family portrait from reused materials. It was a loving gift to the museum. He pointed out particularly the tiles that he had salvaged from the demolition of a fine old antebellum home in Selma, Alabama. A Black family could make a living from scrap metal and stuff thrown away. Sam McMillan painted a different portrait on the valance, cheerfully integrating Black and White children playing together. Truth is, as the White saying about Black relations says, “They were almost like family,” emphasis always on the “almost.” Kids might play together on the farm in Shorty’s youth, but they seldom mixed except when a White man forced himself on a Black woman. There was much to weep about in the Lawson family. But they knew that when one was crying about troubles, their family and Randolph would be there to help. Paternalism cut two ways. “Kenny took care of Mr. Randolph, too, take him home when he was drunk”. Miss Virginia say, ‘There he goes again.’” (Carolyn Lawson) If the children brought on the trouble themselves, there would be serious scolding, seldom anything more.

Shorty taught by doing, “Actions speak louder than words.” A youngster could safely learn most every lesson of life by looking up to and following Shorty’s actions. The children were nurtured by their parents and the idyllic world of rural childhood where wild and domesticated animals and the larger natural world filled each playful spirit. They were relatively isolated from society’s prejudices, free to explore with siblings the creeks and woods that mystified, challenged, excited, and delighted them. But they had to grow up fast. They often heard a parent say, “This is the last piggy-back ride because you are a big girl or boy now.” And then their Daddy died. Their Mother struggled to provide for her family. Each child had to help out.

Nature’s Lessons

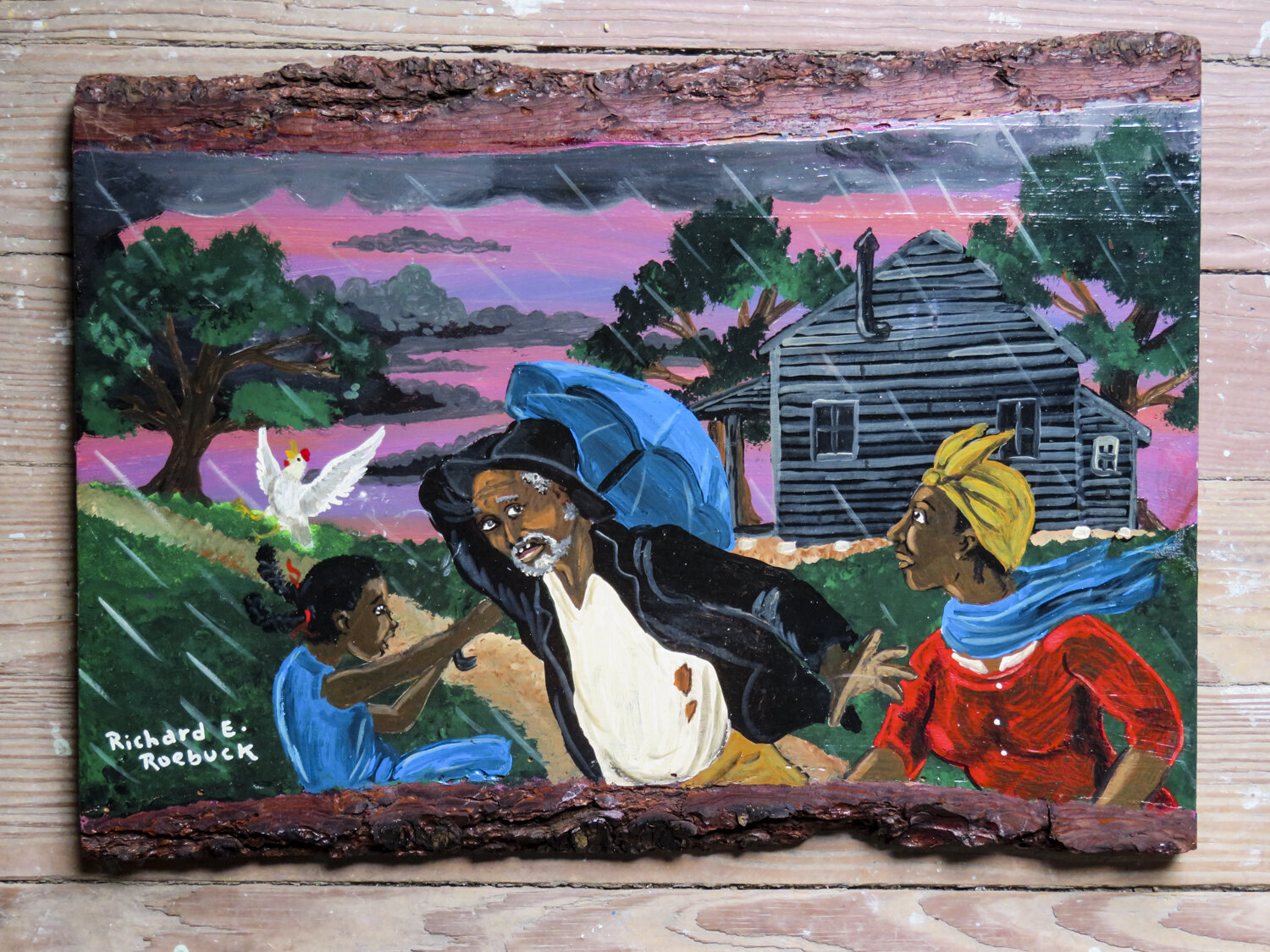

The children learned matters of life and death. Watch out for snakes, especially a copperhead camouflaged in the woods. There’s a snake hidden in the mottled paint. “Parents don’t teach kids that stuff nowadays, just keep them inside, don’t let them play in the woods. That’s a shame.” (Carolyn Lawson) There were lessons in the weather, too. Good weather the Lawsons worked, but kept an ear out for the rain crow. “Daddy told us if we heard a rain crow, it was going to rain, and it almost always did.” (Carolyn Lawson) If it came up a purple cloud, a bad storm was coming. Everyone had to get in a safe place. Jasper and Irene saw a man get killed by lightning over at Turbeville, and lightning rightly scared the Lawsons. If it was just a shower, still someone had to run to the house to get the clothes in. Worst that happened to most folks was getting caught in a Sunday downpour and ruining their best clothes over at the Church of God in the Wilderness. By knowing clouds, the children could tell when it was safe to play in the rain or wait for a happy rainbow. They believed there was gold at the end of the rainbow, chased after many a one, never found gold, but learned a lot from the adventure. Maybe the gold was just for people what owned the land.

If the weather turned hot and dry for several weeks, crops suffered. Vegetable gardens burned up. Livelihood and food supply were threatened. If the drought continued, the community got desperate; it was time to kill a snake and hang it in a tree; if you repented from sin and prayed to God, that snake was supposed to bring rain. There is one hanging in a tree in a painting close by. A few days after a rain was a good time to fish, not right after, let the mud settle out, but the water still high. The children would head for Crooked Creek to catch Knot Heads.

A Lot of Fun

The Lawsons’ pleasures sound too good to be true. Shorty went to the State Fair. It was after tobacco was sold so Shorty had extra cash. He won all the tests of strength, but lost money to a carnival barker. Most pleasures were free. Throw small rocks up in the air at dusk to see bats chase them. Chimney Swifts didn’t chase rocks. On summer nights they caught lightning bugs, kept in jars in their bedrooms. The magical flashing lights evoked dreams of other creatures to befriend or catch.

An unusual pleasure was swimming. Most Black people were afraid of water; didn’t know how to swim. Shorty was a powerful swimmer, saving several people from drowning. He loved to swim and taught all the children. But he had rules. “If we went swimming, one of us had to stay on the bank and watch out for the others. Daddy would hide in the bushes to be sure we were following his rules.” (Carolyn Lawson) But there was nothing like fishing; Carolyn became an accomplished bank fisher, caught more fish than people with fancy equipment. The wild creatures often told her what to do. These days Carolyn only gets off work July 4th. That’s fishing time. She may teach her grandson to fish if he pays attention like in school.

Fish stories make you laugh, catfish in the old pond over four feet long. Shorty and Randolph gigged bullfrogs, made Randy get in the water to scare the frogs up on shore. Randolph took to shooting them with a 22, laughing all the while because Randy was afraid of getting shot or bit by a snake or something nobody knew what it was. Some events are only funny years later. Once Randolph told Shorty to break a pair of young mules, but he wasn’t clear that he meant to rotate the mules so they didn’t get over worked. “Shorty and the boys took turns plowing, kept both mules at work without a break for a solid week. Those mules were never much good after that.” (Donald Hester)

Big Room: Work and Prejudice:

Ask people to describe him, they say right off Shorty was tireless, steady and swift. He was a hard worker. Count on him to do more than his part. Strongest man ever seen, could dead lift a 200-pound bag of fertilizer with his teeth. Shorty and one mule could do the work of a dozen men. Whether it was tobacco, hay, hauling, or plowing, Shorty was faster and better than anyone else. When he broke these hilly fields under a boiling sun, he and his mule were one with the earth. There was no “quit” in him. He often plowed well into the night under moonlight. When he worked the woods, some folks thought he must have had a magic ax he downed trees so fast. But if you worked with him, you saw that the only magic was his skill, ingenuity, and determination. And he could make mules do things others couldn’t; he could snake logs, never getting hung up. He wasn’t exactly a mule whisperer, but he knew every mule inside and out, which direction one swished his tail to chase flies or what the mule really meant when he snorted and nodded his head. Shorty knew the mule’s pace reflected the man, so mules plowed faster and straighter for him than for other people.

Shorty loved hard work. He thrived on it. He knew it distinguished him. He got pleasure from outdoing all others, especially lazy and uppity White boys. “For a few years there was a White tenant farmer, Harry Clark, who oversaw Shorty and me. He always assigned himself the easiest job or no job at all, and he just loved to order us around. Shorty and I bonded with dislike for him. And I adopted Shorty’s value of hard work.” (Randy Hester) He worked every job available and made enough money to provide things for his family, from an electric stove to a television. There were plenty of families in the county so poor that Beggar’s Lice wouldn’t even stick to their pants; but Shorty’s was an exception. Getting his family ahead was important, but he resisted dollar-worship as “the Negro stood in danger of being dazzled by the shimmer and tinsel of superficials.” (Anna Julia Cooper) For Shorty hard work was its own reward.

Row Work

Shorty loved to celebrate the completion of work well done. He would lead an impromptu jubilee when a tough week of plowing was finished. “We’d race our mules to the pond, strip, and go for a swim while the mules drank.” (Randy Hester)

Most of the regular work Shorty did was row work. Plowing, planting, weeding, laying by, suckering, worming, pulling. All row work. To grow 30 acres of tobacco required walking over 60 miles row by row for each task. Add in corn, hay, beans, milo, and other crops, you walked 80 to 90 miles every week for six months, not just walking but planting, hoeing, or harvesting while you walked, from dawn to dark. At sunrise rows offered a beautiful fresh start, fueled by night’s rest. By sundown purple shadows were dulled by exhaustion. By the end of May weeds were outgrowing newly planted tobacco. Row work turned to hoeing. Everyone, including women and children hoed. Chop the weeds without hitting the tender tobacco plant, pull the uprooted weeds into the middle of the row, then hoe up dirt around the bare base of each plant. Then do the same for the next plant. Finish one row, on to the next row, and maybe tomorrow the next field. Every day was the same row work for two weeks.

Pulling bottom leaves was the hardest, most humiliating row work. Purvis Young painted this perfectly with endless rows of repeated action. Bend over. Pull two tobacco leaves, one half-buried in the dirt, and, in one motion, store the leaves under your left arm. Repeat dozens of times, bent over fully at the waist, only standing upright when you can hold no more leaves under your arm. Walk to the slide. Put your tobacco leaves in a neat pile inside the slide. Firmly tell the mule to “come up”. Repeat the same action for five hours in the morning and five hours after dinner, for several weeks. “I was never as fast or skilled as Shorty, but I learned to match his endurance, just one gift he gave me. He was pleased to show me how to work beyond exhaustion. Shorty could pull and hold about a dozen leaves in each hand so he mastered pulling two rows at once. He pulled two rows; I pulled one, and he always finished his two rows, then helped me finish my row. Always. Even when I was in high school.” (Randy Hester)

Powerful Strong and Fast, with Grace

Shorty Lawson challenged and/or inspired most everyone who knew him. “He was the hardest working man I have ever known. One day I told him that. He smiled. Later that day he said, ‘Mr. Randolph is the hardest working White man I know.’ I asked if that meant my daddy worked hard, or just that most white men didn’t. He smiled again.” (Randy Hester) Annie matched Shorty’s skill and capacity. She was acknowledged for stringing tobacco. Nasty, tiring work, it required rhythmic quickness and aggressive gentleness, a dexterity less considered in field work. “Everywhere I work, people, if they knew Mama and Daddy, they expect me to do more and do it better than anybody else.” (Carolyn Lawson)

The tractor changed Shorty’s world. It replaced mules for most work, hauling more, plowing faster. A John Deere symbolized progress, but mules were still essential for work in close quarters. Shorty taught Randy and his boys to care for them even as they became less valued. He saw things come and go. As a boy he planted tobacco with a peg. As a man he dug a hole, planted, and watered the tobacco slip with one pull of a metal trigger. Inventors were creating machines with unimaginable power and speed. But machines brought new dangers; a crop duster plane hit a power line and crashed at Hesters Store, killed the pilot. Within their community the Lawsons embodied all the power, speed, and grace that anyone could envision. They did what others in the community did: make wood and do household chores, tend their garden and each other. But they kept right on working when a local politician offered up his stump speech; he was not there to solicit their votes.

The Struggle Out There

The summer of 1964 was different. Randy came home from college full of Freshman ideas. In Raleigh he began to conceptualize inequality. He was exposed to roles White people played in the Civil Rights Movement. For him abstracted racial injustice in the media was personal, peopled with ones who loved and mentored him, and he wanted to discuss these matters with Shorty. Shorty tolerated Randy’s talk, but it didn’t make much sense even when the Civil Rights Act was signed by President Lyndon Johnson just before July 4th. It was miserably hot, and tobacco needed suckering, worming, and pulling. Randy persisted. In 1965 he volunteered to lead an After-School Program for the local Office of Economic Opportunity in Chavis Heights, the Black Ghetto in Raleigh. Shorty was mystified. At the end of the 1965 tobacco season Congress passed the Voting Rights Act after confrontations at the Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama dramatized barriers preventing Negroes from voting. Change was slow. Shorty voted only after Curtis Bradsher started picking him and Annie up and driving them to the polls.

Likely Shorty never was confronted with a “Whites Only” sign, an indication of the isolation of Hesters Store where the front door served everyone, and segregated territories were understood by all. White men conversed in a circle inside the store. Negroes gathered under the big oak tree outside. Open to all men, women seldom entered the store. In Roxboro there were many places that served only White people. “Toufie’s Hot Dog Place behind the taxi stand only serve us from the back side.” (Carolyn Lawson) To avoid swimming with Blacks the White community built a private swimming pool in Roxboro. That didn’t affect mixed-race swimming in the ponds at Hesters Store. “The inability of one race to exterminate another gives rise to mutual understanding, reciprocity, and liberty.” (Anna Julia Cooper)

Shorty saw Chain Gangs of Black prisoners, guarded by white men with shot guns, but he knew his place, commanded his place, and stayed out of trouble. Locally Jim Crow laws outmaneuvered the Federal laws that sought to guarantee equal rights for all people.

Black, White, Landed and Tenant

In rural North Carolina almost all men farmed during Shorty’s lifetime. Black and White, land owners and tenants, interacted intimately daily, often working side-by-side, but the social distinctions between Black, White, landed and laborer were clear and impenetrable. These distinctions determined income and net worth; dress; personal privilege; access to power; car, home and appliance ownership; church and school attendance; where one shopped; and the women a man controlled.

Shorty knew firsthand the racial tension that sexual relationships created. He likely had been told about the lynching of Edward Roach in 1920 for attempted rape. He could not avoid the fear that ran through his community after Henry Marrow was murdered nearby in Oxford in 1970. Nineteen seventy. Although disputed, Marrow reportedly had made an ugly remark to Larry Teel’s wife. The Teels then brutalized and killed him. And Shorty knew that Annie was a strong survivor in spite of the seeming powerless place of Black women. She nurtured and gave the family strength. She could have been one of the tigers that Thornton Dial painted symbolizing the struggle.

Shorty understood the struggle and was pleased that C.T. Vivian compared Randy to H. Rap Brown, but only after he was told who both Vivian and Brown were, “You got room to be a troublemaker.” (Shorty Lawson) He finally acknowledged his influence when Randy moved into Chavis Heights and led fights to stop a freeway and Urban Renewal Clearance that threatened to destroy the homes of thousands of Negroes, but he didn’t bother with the abstraction. His response: One day he touched Randy’s hairy arm covered with sticky tobacco gum, comparing it to his hairless, gumless arm, “There are advantages to being Black.”

Boys’ Bedroom: Snakes, God and the Devil:

Snakes, Haints, Preacher Wiley Bradsher

Although there were dangers everywhere, the Lawson family was most afraid of snakes. A moccasin’s bite could kill you, and it was within striking distance before you ever saw him. Snakes occupy this room. Not a single one will bite. There were ways to mediate other fears, but nothing could protect you from snakes. To keep ghosts from entering your house, paint walls “haint blue” like this room; electric blue is even more effective. Haint blue keeps bad spirits and witches at bay. A rabbit’s foot in your pocket helps avoid ill fortune and brings good luck. If you are kind to wild animals, they rescue you from danger. And you know that Jesus died to wash away your sins. Read selectively, the Bible offers remedies to all sorts of fears. You also have some measure against the fear of servitude and death: look over Jordan for angels or haints coming to take you home, either returning you to Africa or delivering you to heaven. You can forestall death by returning the owl’s hoot.

The Preacher over at the Church of God in the Wilderness said that if you avoid the ungodly, the sinners and the scornful, whatever you do will prosper. He had Psalm 1:1 inscribed on an obelisk where the Lord saved him a few miles from here. To be sure everyone contributed generously to the church Preach Wiley Bradsher played to the primal fear, a black snake named Sambo kept in the church to encourage the congregation. Preach was the moral authority because God had stricken him for his sinfulness and saved him for his faithfulness. He feared that the automobile would be the ruination of the Black man so he hanged a car from an oak tree at the church. Lynching the car touched nerves, past and present.

The Church of God in the Wilderness shaped the Lawsons’ faith. It provided an amazing grace for Annie’s family and hundreds of congregants, comforting the Lawsons during their most desperate times. But snakes remained a fear without a remedy.

Desire, the Devil, Sins Washed Away

Drawings of people and cars were left for years on the west wall of the boys’ bedroom. Carolyn Lawson identified the artist. Shorty’s half-brother, Larry Dixon, was a big Carolina fan. Carolyn had no idea why he drew Moses or the White boy with glasses; but the cars were easy to explain. All the boys wanted cars in spite of Preach Bradsher’s warning. Larry reconciled the conflict by drawing a license plate proclaiming “I love God” on his Ford convertible. His Bible was left here, the 23rd Psalm marked by a red “X”.

Why did Preach worry about car damnation? He must have observed how quickly it had invited all manner of missteps. It made Black men indebted consumers; Bradsher preached buying land instead. He saw land ownership as power. A car loan distracted you from long-term security; car envy invited the Devil. Annie’s family attended Bradsher’s church and believed in him. Shorty abandoned his car soon after he married Annie and never owned another one.

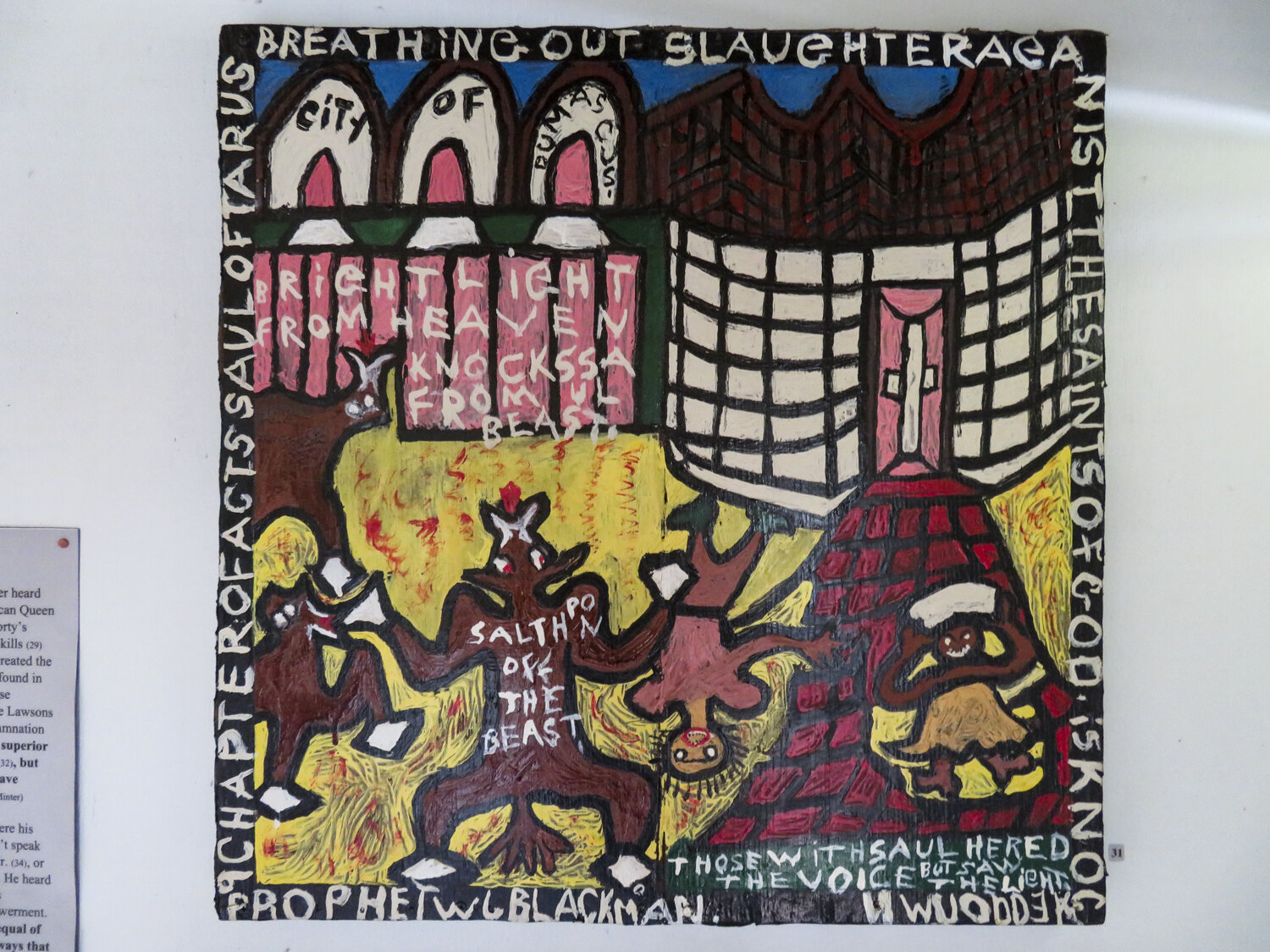

R. A. Miller depicted the Devil as eager to tempt you with something you had no business wanting so bad. And the Devil’s friends had so much fun. Just consider the expression on Devil Rooster’s face. Annie’s family believed evil could be washed away. Baptism cleansed mistakes, but temptations were ever-present. Each person had to choose between Sin City and Salvation-Ready-Mix where Grace, Mercy, and Love poured a solid foundation to combat Greed, Envy, and Pride. Most temptations were things just out of your grasp, and the Devil had the power to help you acquire short-term pleasures. The result: a soul tortured by injury, a maimed body, nightmares, and monsters. Preach knew this first-hand.

Trying to Understand Good and Bad

There were two bunk beds to sleep four, a homemade closet and no window. Cramped quarters. Plenty of boyhood devilment. Experience taught Shorty plenty about the complexity of God and the Devil. He saw both good and bad in everyone and everything. For example, most snakes were harmless; several poisonous; and a blessed few were downright beneficial; yet they all scared you. Shorty explained quite directly why Jerry Clark was often mean as a snake, “He just gets the Devil in him, that’s all.” Little more was said about the Devil.

Shorty ordered the world in similar practical ways based on what he observed to be true rather than what others imagined. Working fields, he talked about the day’s work or Shotgun Howerton when he drove by real fast, kicking up a dust storm, “Hope the kids get out the road.” Working row by row at the edge of fields exposed folks to a lot of sky and wildlife so he would talk about the weather or birds he saw, “Big cloud cooled things off.” That might remind him of the whip-poor-will’s weather predictions or how he called turkeys.

He liked to talk about flying; the farm was in a north-south flight path, and the novelty of airplanes was worthy conversation. “Once he asked if I believed people could fly like hawks or owls. I didn’t think so. He responded that even if he could, he was staying put. I wasn’t quick enough to connect this question to his song about all African children got wings.” (Randy Hester) Years later an architect studying Gullah buildings told Randy stories she heard about slaves in the Sea Islands who would say some magic words and fly right out of a field into the sky. An owl swooped down, gave them wings, picked them up, and off they flew like a hawk all covered with whatever they were harvesting. With time, all the children had apparently lost their wings or forgotten the secret words.

Shorty said there were too many things we couldn’t understand. He didn’t see how a groundhog could tell the weather more than a month ahead, or why turkeys hardly ever responded to his call. It was hard to know how things came to be as they are or how the world got made in a week or why Adam and Eve went right off to sin. Maybe the mess they were in was caused, not by a serpent, but by Eshu, the flute-playing African God who created contradictions, uncertainty and conflict.